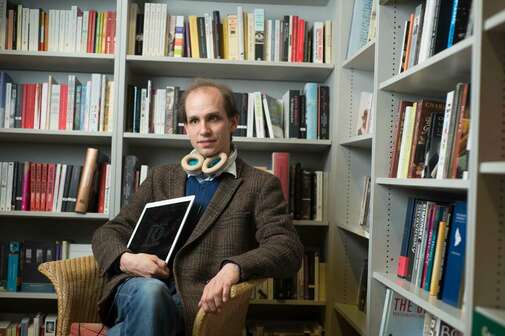

If humanity were to go extinct, how bad would that be? How should we prioritize research and resources across many different threats to the long-term future of our species? How can we make trade-offs between the number of people who are alive now and the number who will ever be born? These are the ethical questions that form the backbone of my research. Existential risk research aims to promote the long-term interests of humanity by better understanding the threats to our future and how we might respond to them. It owes its existence in no small part to the field of Population Ethics since it was in the writings of people like Henry Sidgwick and Derek Parfit on this subject that people first began to engage with the mismatch between the limited efforts being taken to mitigate the risk of human extinction and the enormous ethical costs that such a catastrophe would bring. My research into this area began via the same route and my own attempt to resolve some of the intractable problems currently facing certain views about population ethics. In particular, my PhD thesis explored the hypothesis that there may be multiple irreconcilably different values that governed what it would be best for us to do when it came to future generations. Some of these are reducible to a single conception of ‘utility’ or ‘well-being’ while others cannot be so reduced, although they may still form part of a broader conception of what we call ‘Quality of Life’. Human extinction, I argued, would be doubly tragic because it would not only involve the loss of all the potential future happiness that members of our species might go on to experience, but also these other, less tangible, goods that related to our growing achievements, our aesthetic sense and our ability to engage ethically with the universe around us. I still believe that this is, if not the right answer then, at least a step in the right direction to understanding the tragedy of human extinction. However, since I started working more deeply in this field, as a Research Associate at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, I have come to question whether my role as a philosopher should be coming up with the right answers at all, or whether I can put my talents to better use helping others to understand the implications of their own ethical position. I have thus started to work a lot more at understanding as much as I can about the nature of the threats that we face and on connecting these to the wide variety of ethical perspectives that exist in the world. In a recent paper, co-authered with Phil Torres, we examine a range of these perspectives, from virtue ethics, Kantian deontology, contractualism and consequentialism, and argue that there are at least five ways in which we might view human extinction as bad, and that all of these perspectives gave us reasons to be extremely sensitive to at least two of these; although no perspective seemed to care about all of them. These were: 1. Human extinction would likely involve a massive loss of life and also a loss of auonomy and hope to very many people. It would thus be amongst the greatest harms that we could conceivably cause for most people now living. 2. Human extinction would remove rational agency and human understanding form the world as we know it, and potentially from the entire universe. It would be the frustration of every, or at least almost every, purpose or intention people have ever had 3. Human extinction would be the end of our collective story as a species and a violation of the intergenerational social contract in which we gratefully receive the benefits and wisdom of those who have come before us and seek to pass on even more of these to those who will come after us 4. Human extinction will cause many potential future people, who could have experienced even more potential future happiness, never to exist 5. Human extinction will remove from the world all of the best things in life that we have special reasons to value and treasure, from science and art to romantic love and universal compassion. Of course, different theories may still disagree about just how much worse human extinction might be to other things. However, even arguing that this is important can imply a bias towards ethical theories that care more about relative values (like consequentialism) rather than those that see value as absolute. As we point out in the paper, Kant would almost certainly have felt we had a perfect duty to prevent human extinction if we could, and whilst that may only place it on the same level as our duty not to murder it still places it remains a perfect duty, which seems like something we should care a great deal about. This convergence can sometimes break down when one turns from the question of whether human extinction is bad to how we should go about avoiding it, however, even here the differences between ethical approaches often appear to be less in practice than they appear in theory. Partha Dasgupta and I have recently been putting together a symposium of papers about population ethics as a global challenge. We have submissions from all sorts of ethical traditions, including Utilitarianism, Human Rights theory, traditional Akkan philosophy from Ghana, Intergenerational Justice and Non-Ideal Theory. These different approaches diverge on many points, such as the relative importance of conformity in reproductive decision making and the distribution of the burdens and benefits of parenthood. However, all agree that global population is becoming an increasingly serious issue that is not only driving destructive environmental change but also holding back poor people and developing communities from increasing their standard of living. These authors also agree that this has now reached such a point where the ethical imperative to have fewer children is one that people can see and understand for themselves, so we need to discuss population just as much as a problem for personal ethics as for public policy. Since realizing this, I have sought more and more to take my work outside of academia. In 2017 I took part in the BBC's New Generation Thinkers scheme and was able to put together a radio documentary on population ethics that was broadcast last month. I also helped to found, and am now an advisor to, the All Party Parliamentary Group for Future Generations, which seeks to represent the interests of future people in the UK parliament. I believe that both in terms of population ethics and existential risk, the world is reaching a tipping point. It appears that as many as 18% of everyone who ever lived might be alive right now. That is both a very scary statistic, but also a sign of how much potential we have to change our future. We need to start seeing population ethics as less about criticising others for their reproductive choices and more about helping our species navigate the many risks we face and achieve our true potential. Simon Beard is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at University of Cambdridge.

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed